HE is seemingly being ever more exposed to the use of metrics. This is most obviously the case in the current development of the TEF (Teaching Excellence Framework) where often vague, tangential datasets are to be used as a measure of the quality of teaching. One of the stated purposes of such frameworks is to offer institutions insights into how to improve their processes. However, one of the main problems with the use of any type of summative evaluation is that it might offer insights into patterns, and hence ‘what’s’, but has little to offer in terms of ‘how’ or ‘why’. Evaluations can also begin to pervert the processes they are intended to improve as they become part of the ‘accountability-complex’,

The paradox is that the accountability fervor meant to assure performance can have direct and indirect consequences that undermine it.’

(Halachmi, 2014)

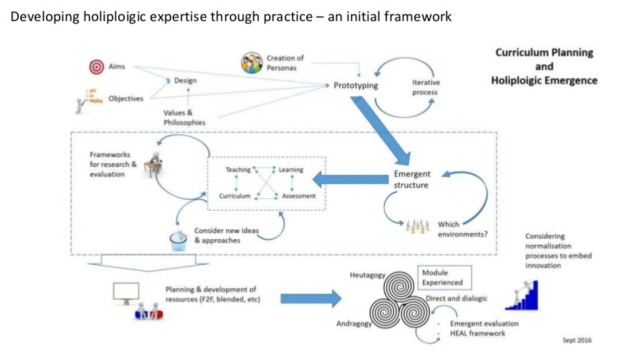

A number of different approaches to programme and module evaluation have started to emerge, including the inclusion of student perspectives. Here, I outline a view which takes this as a starting point and considers the potential of a theoretical framework called Normalization Process Theory (which was developed within the health and social care area) to help develop holiploigic practice. The process I am currently developing starts from the definition of sense-making of Klein, given by Snowden,

‘Sensemaking is the ability or attempt to make sense of an ambiguous situation. More exactly, sensemaking is the process of creating situational awareness and understanding in situations of high complexity or uncertainty in order to make decisions. It is “a motivated, continuous effort to understand connections (which can be among people, places, and events) in order to anticipate their trajectories and act effectively.’

This stresses the ongoing nature of sense-making in an attempt to understand the evolving complexity of a context. In the case of a masters module, sense-making becomes a process of understanding experiences and perceptions of students as their work develops within a module, rather than waiting until the end of the module to gain retrospective perspectives.

To develop a framework for sense-making, I suggest here the use of Normalization Process Theory (NPT). This theory might not always work for sense-making activities, but where the focus is on embedding a change or process, it is ideal. NPT was developed by May and Finch (2009) as a way of understanding and assessing innovational change in health and social care contexts. It distinguishes between implementation (a relatively straight forward process), and normalization such that the innovation or change becomes embedded (a very difficult shift to achieve). It is in the gap between implementation and normalization that ‘zombie innovation’ (Wood, 2017) occurs, senior leaders believing that organizational proclamation leads to embedded day to day practice. But often, such proclamations merely lead to initial implementation, followed by ‘compliance under surveillance’ – i.e. the change will be present in official documents and assurance of practice, but not in day to day work. NPT is structured into four elements:

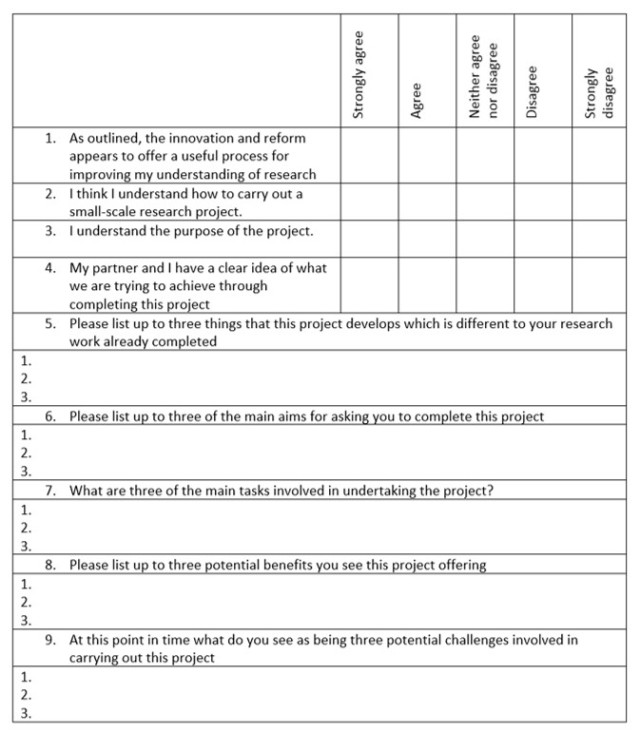

1. Coherence – this is the element of using a new practice which involves understanding how the new practice is different to what is currently done, and also being able to clearly understand and operationalize the aims and objectives of the new practice.

2. Cognitive participation – this is the work individuals do to develop a collaborative approach to the change which is being undertaken. Are they able to create a successful community of practice?

3. Collective action – this relates to the resourcing and collective work done by a community to embed practice. It includes the development of new knowledge, understanding how the facets of a change can be brought together and generation of new practices.

4. Reflexive monitoring – this is the appraisal work a group and individuals do to understand the processes and outputs of a change, as well as considering how localized changes might be developed further to ensure successful embedding of new practice.

By using these elements to sense how learning across a module is developed, it might be possible to understand how learning and skills are becoming embedded as the module is being experienced. This leads to the potential for changes and development in real time.

The example here is a module in an MA International Education programme. Early in the course all students complete a core research methods module. This module allows students, many of whom have never encountered research methods in their prior university experiences, to gain a foundation across approaches in education. An assignment concludes the module, based on asking students to create a research project plan, before piloting a single data collection technique and evaluating it.

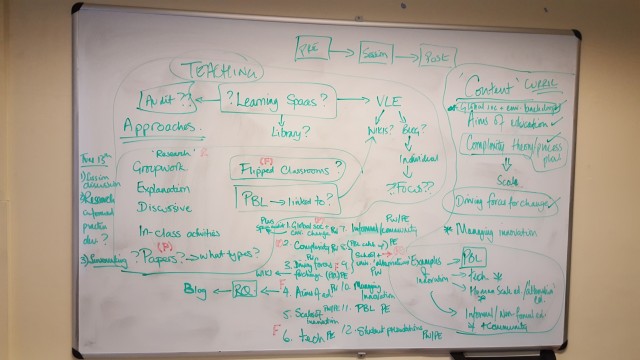

Whilst the research methods module offers a positive initial experience of research methods, it is a large jump from this to a dissertation study of 20,000 words. As a consequence, those students undertaking an optional pathway in innovation and reform in education are asked to complete a research module (30 credits). They work in pairs to develop and complete a small-scale research project based on an issue relating to innovation and/or reform. Sessions are led as group tutorials, covering and developing issues the students feel they need further help with, as well as reporting back to the group on a regular basis to discussion ideas, plans and execution.

Given the challenging nature of the project for many, whilst it would be possible to evaluate the module at the end of the process, it would be far better to sense-make throughout the module. Therefore, given that the nature of the project is to help students embed new practices as they move towards their dissertation, I am currently beginning to think about the potential for NPT to act as a positive framework. The intention is to use four short questionnaires at points over the course of the module, followed by a focus group on each occasion as a way of understanding the nature of student learning and practice development. The first questionnaire, focused on issues of coherence, is given below as an example,

The intention of this phase is to ensure that the students understand what the purpose and aims of the research project are. If students do not understand this then we are building on a poor foundation from the very start of the process. By investigating this early on I can work with the students to sense the level of confidence, knowledge and conceptual understanding on which they can baser their work in the coming weeks.

Once we have started this process, in a couple of weeks’ time, we will move on to consider and develop a sense of participants’ emerging work together, and the degree to which the taught sessions are helping them become part of a wider research community.

References

Halachmi A (2014) Accountability Overloads in M Bovens, R.E. Goodin & T. Schillemans, The Oxford Handbook of Public Accountability, Oxford University Press.

May C and Finch T (2009) Implementing, embedding, and integrating practices: An outline of Normalization Process Theory. Sociology 43(3): 535–554.

Wood P (2017) Overcoming the problem of embedding change in educational organizations: A perspective from Normalization Process Theory. Management in Education 31(1): 33-38.

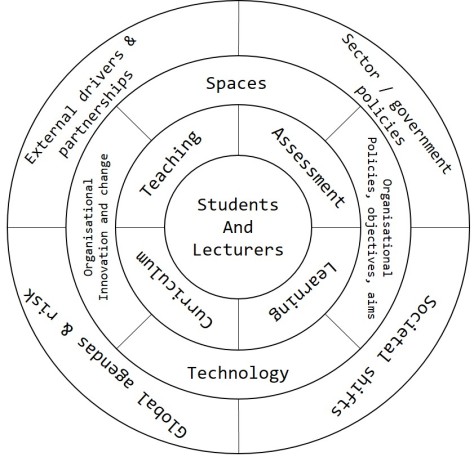

I argued that we should move away from ‘teaching and learning’, and back to a reformed notion of ‘pedagogy’

I argued that we should move away from ‘teaching and learning’, and back to a reformed notion of ‘pedagogy’